The last decade has seen a rapid rise in attention toward the global status of insects. Insects comprise the majority of terrestrial biodiversity and are instrumental components in nearly all ecosystems, from pollinators and decomposers to food for other trophic levels.

We know very little about many insect groups, but we know a great deal about butterflies. They have long been of interest to naturalists and have been monitored worldwide for decades. My research pairs population-level data with genomic and experimental approaches to understand how butterflies are faring in a rapidly changing world.

Multi-decadal changes in insect biodiversity from historical datasets

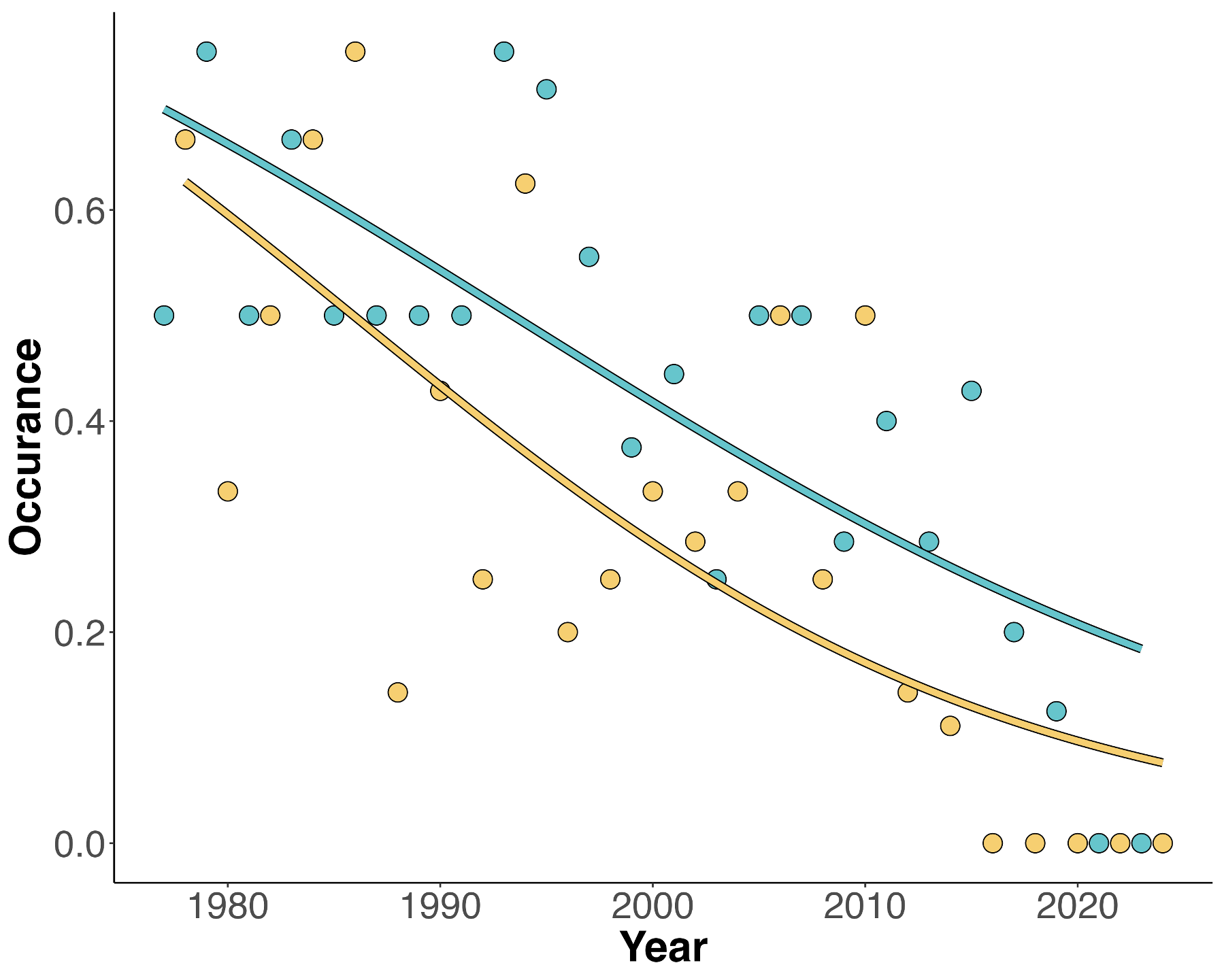

Insects are the exemplars of boom or bust population dynamics, where in some years, a particular species is nearly absent, but in other years, they dominate the landscape. Cycles like this complicate our understanding of responses to global change because, over short time spans, it is difficult to disentangle expected population oscillations from unexpected declines. My research uses long-term datasets and historical records that span beyond typical population dynamics to understand the trends in insect populations driven by Anthropogenic change. Datasets like these offer great insight into the realized impacts of global change. I use data from, but also contribute to, butterfly monitoring programs like the Shapiro transect, NABA butterfly counts, and PollardBase, and I feel strongly that the continued collection of datasets like these is essential for fully comprehending biodiversity loss.

Resilience of montane butterflies to climate change

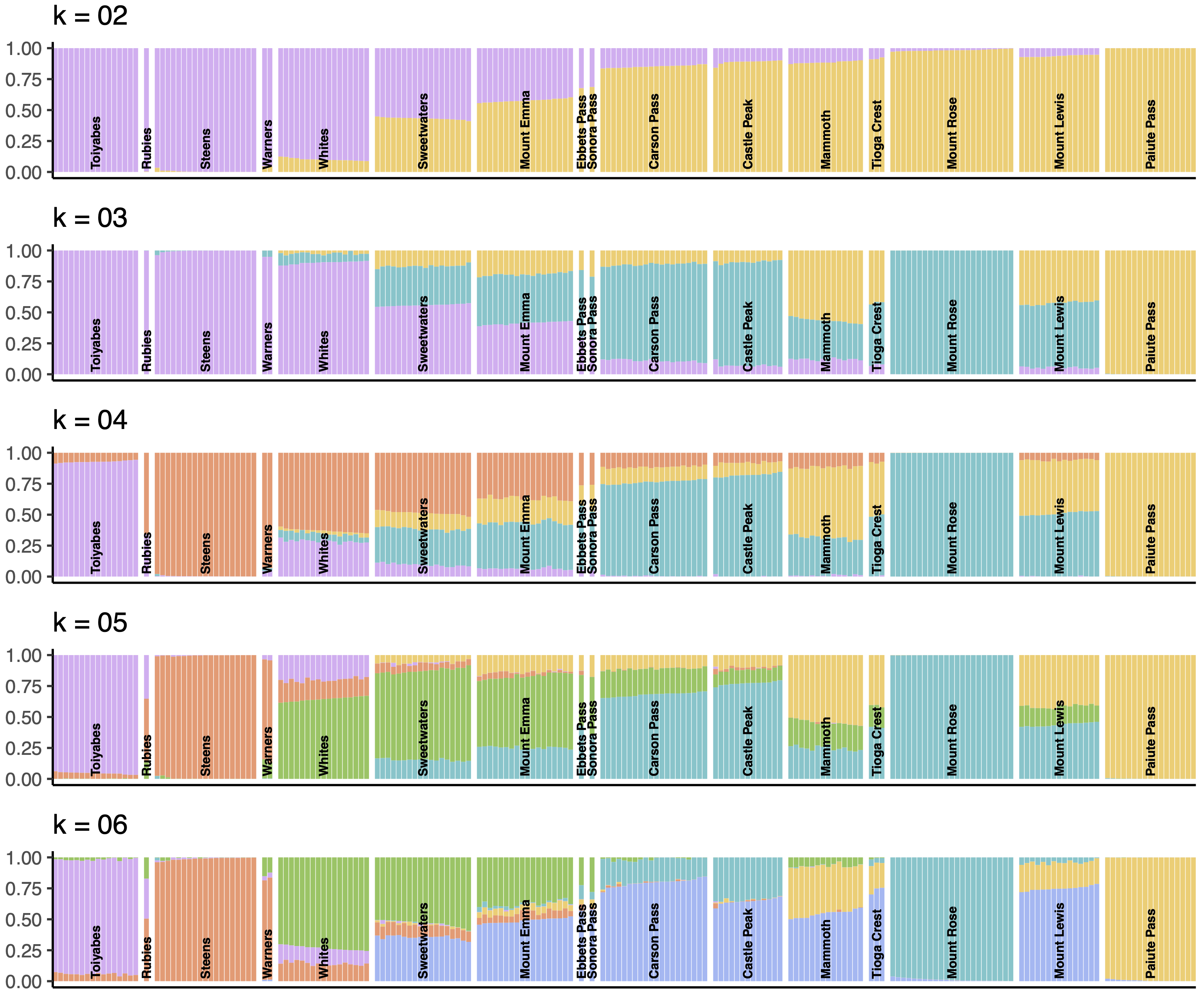

Populations on mountaintops have long been predicted to be among the most vulnerable to climate change. These species cannot move further upslope to track changing environments; to persist, they must adapt. Insect populations generally contain many individuals and reproduce more quickly than larger-bodied animals. If any organisms can be expected to evolve and adapt, it is insects. My research utilizes historical datasets and next-generation sequencing techniques to ask how weather drives population dynamics and local adaption in montane landscapes.

Conservation of butterflies in multifaceted landscapes

The drivers of insect decline are multifaceted. Many populations face multiple stressors at once, and while the additive effects of threats are alarming, the interactive effects of multiple stressors may be detrimental. My research addresses these questions, using the California Central Valley as a model landscape, where land use change, pesticide exposure, and climate change are all important factors. I use experimental and simulation approaches to understand both additive and interactive effects in such systems.